~~~~~~~~~

The Story of Polioptics is a 10-part Web narrative based on a multi-media presentation — POLIOPTICS: Political Influence Through Imagery, From George Washington to Barack Obama — that debuted on college campuses in 2009.

In Part 3, the “Mere Exposure Effect” showed us how images create a positive reaction among viewers exposed to something new; the good vibes increasing the more familiar it becomes. It’s what happens when something becomes part of our daily fabric, no longer alien, like a comfortable chair.

Beginning in early 2007 and throughout 2008, the team marketing Barack Obama transformed a person known to only few and made him fit the American voter like a comfortable chair, at least among 53% of the electorate and the 66,882,230 people who cast a ballot for him and running mate Joe Biden.

The 2008 margin of victory was much greater than 1976, but the effort to market the outsider through command of the then new tools of electronic campaigning was in many ways the same. A campaign based far from Washington, D.C. managed by a small circle of advisers. A candidate new on the national scene known to few outside his geography, but with fresh packaging and broad awareness. The mere exposure effect in action. His name was Jimmy Carter and he too, as well as his successor, Ronald Reagan, fit America like a comfortable chair.

Our story picks up in 1976. It’s just after the Bicentennial. Gerry Ford is trying to hold onto the office he inherited from Richard Nixon. Television – and the evolution of the national network evening news programs— is changing political marketing. “Paid media” and “free media” are entering the political lexicon.

Paid media is is the product that political consultants create with their film cameras and editing machines, along with print and radio ads and, later, direct mail. They broadcast the message to likely voters in costly 30-second TV productions during prime viewing hours. The spot below for Jimmy Carter is quaint by today’s standards.

Free media, on the other hand, is how candidates get their message out without spending money to buy airtime. It occurs as a part of the the campaigning process when politicians hold open-press events in various media markets. Balloons, smiling babies, and handmade signs are part of the colorful mix.

Money is spent, of course: on dispatching advance teams around the country for several days to orchestrate the movements and choreograph the visuals to match the day’s message. This is followed by flying the candidate, his staff and the traveling press corps in a chartered jet in hot pursuit. At the height of campaign season, the cycle repeats two to four times a day, or more, during round-the-clock, get-out-the-vote nonstop fly-arounds. As logistically complex as it is, compared to writing checks to TV stations to air your spots, it’s exposure on the cheap. It comes as well with the added benefit of third-party local press validation of campaign themes.

After the event, news crews from local stations transmit by microwave or physically carry the footage they shoot back to the station. In the case of national networks, they courier the tapes or or uplink the footage via satellite back to the bureau. Either way, the raw feed gets churned through the editing machine. The good stuff gets logged and extracted, cobbled together in what’s known as a ‘package.’ The correspondent tracks a voice-over to the edited cuts. The piece is readied for air, cued by the anchor. In the process it becomes, in effect, a commercial for the candidate produced free of charge.

In 1976, more than three decades ago, candidates were already established free media content creators. The networks served as the conduits of their message. Check out the video of Harry Reasoner introducing a package by Sam Donaldson reporting from Plains, Georgia on the ABC evening newscast on July 5, 1976. Reasoner tees up the story at the 07:55 mark of his broadcast in the archive clip below. For a trip back in time, watch the whole show, and its commercials, for the full effect. This old package about a day on the campaign trail seems as far removed from The Rachel Maddow Show as Avatar is from Saving Private Ryan, but it says a lot about where we are now.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uby79EagPn4&feature=related

When videotape replaced film as the standard format for electronic news gathering, or “ENG,” it accelerated the process but didn’t change the paradigm. Gathering news for television still meant dispatching a crew of at least three people to a campaign event: the trench coated correspondent; the cameraman shouldering a bulky camera; and an audio technician, tethered to the camera guy by an umbilical cord, with a video recorder slung over his shoulder and a boom microphone, known as a “squirrel,” held aloft to capture the ambient sound.

The new technology and tape format dramatically simplified the editing process, cutting the time drag of developing and drying celluloid and allowing for multiple angles in a report and synchronized sound from different sources. Free media was in endless supply, as long as candidates — like Jimmy Carter in his “Peanut One” campaign plane — stayed on the move. Every new media market they visited represented a supply of new free media packages destined for air. The packages could air on the noon, six and 11 pm newscasts, introduced by excited anchors thrilled to have their town the focus of the national campaign.

Carter enjoyed several narrative arcs to burnish his message. First, a dose of celebrity was added to the 1976 campaign. Carter’s image recalled Paul Newman’s Butch Cassidy to Robert Redford’s Sundance Kid. Another attractive arc of the narrative was Carter as the nuclear engineer, a graduate of the United States Naval Academy. And for the audience drawn to his folksy backstory, Carter was the peanut farmer turned governor, a cool outsider ready to shake up Washington.

After his election, President Carter enjoyed the kind of honeymoon that many presidents expect from their first year in office. Images of him carrying his bags onto Marine One were a welcome contrast to the image of Richard Nixon’s Imperial Presidency.

Carter made his visual breakthrough with Camp David and the peace talks he held there between Egypt and Israel.

Carter made his visual breakthrough with Camp David and the peace talks he held there between Egypt and Israel.

First, the world saw through released photographs the negotiators sequestered in the Catoctin Mountains. Anwar Sadat and Menachem Begin spending time together opened a new chapter in Middle East history. Following the talks, back in Washington, there was the announcement — a rare public event staged on the North Lawn of the White House — followed by a signing ceremony in the East Room as history was finally inked.

Carter was determined to bring a different image to the White House, one of vigor and activity compared with Richard Nixon, famously photographed bowling alone in the basement of the White House or wearing wingtips on a Florida beach while visiting his pal Bebe Rebozo. But Carter took casual too far. Near Camp David, he fainted in a road race. The picture went everywhere. The message was weakness, as Time Magazine noted:

“Seconds later, an ashen-faced Carter felt his legs go rubbery and just as he began to fall a Secret Service agent grabbed him. Some aides feared he had suffered a heart attack; the White House and National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski were immediately alerted, and there was talk of evacuating the President to a hospital. But White House Physician Dr. William Lukash diagnosed heat exhaustion. The President was taken back to his bedroom at Camp David, stripped, covered with cold towels, and injected with nearly a quart of salt water through a vein in his left arm.”

With the story in Time coming out on October 1, 1979, it was unwelcome imagery a year from Election Day.

It got far worse.

On November 4, 1979, 52 Americans were taken hostage in Tehran. It brought us face to face – via Ted Koppel – with our inability to free our own citizens held in a hostile capital. We tried, and failed, at Desert One. Six months before Carter would face voters, Desert One helped seal his fate.

It was a time before cable, before blogs, before the news cycle became immediate. The covers of weekly news magazines – which now struggle for survival – defined our dinner table conversation. In many ways, they set the agenda. At my home, the magazine would arrive with the mail on Tuesday morning and I would spend the afternoon after school decoding the images, starting with the cover.

What did Americans see on Time’s cover in those pivotal months?

- Jimmy Carter starts out looking bold.

- A potential challenge is in the offing.

- The hostages are taken and it’s the Ayatollah vs. the President.

- A cover illustated to spark fear?

- The president talks tough.

- The president as Gary Cooper.

- His opponent is simply “Ronnie.”

- The opposing ticket emerges.

- As does a headache.

- Time puts the president and his world into a curio box, then focuses in on the man.

- Election day arrives, and America faces The Choice.

- Then, the choice is made and a fresh start begins.

- A breakthrough leading to the hostages’ return, and then American Renewal.

All along, if you were trying to construct a narrative through cover art, you could have sensed where Time’s editors thought the election was headed, mythology in the making.

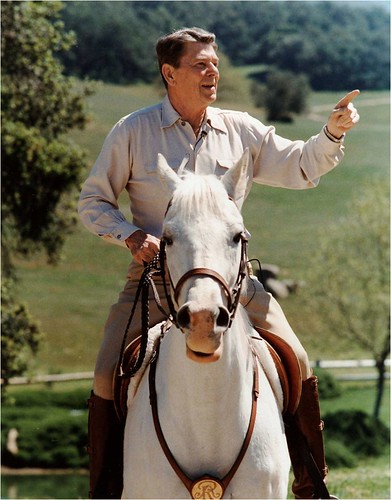

This part of Polioptics started by bringing us back to 1976. It’s now 1981. Ronald Reagan is in office. The camera loves him. He loves it right back. In the movies. As aspokesman. Even about to be shot, he’s smiling. Then smiling from his hospital on the mend. At the ranch, images of President Reagan were every bit as effective as in the White House, especially on horseback.

Reagan on El Alamein, the president mounted on the white horse

It’s why, in summer ‘95, Dick Morris and Mark Penn looked at their polls and suggested that Bill Clinton spend his vacation not in Martha’s Vineyard, where he might have wished, but roughing it, relatively, in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. I packed my bags and headed to Yellowstone to help set up Reagan-like pictures of the president that summer: hiking in Yellowstone, visiting with rangers of the National Park Service and rafting down the Snake River. The Western theme and its rugged symbolism continued into the reelection year of 1996, resulting in shots like this in the plains near Billings, Montana.

Clinton on the white horse, on the plains near Billings, Montana, 1996

As Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton and Barack Obama demonstrated, the road to the White House is long, now stretching over two years from campaign announcement to election day. But the theme of the outsider running against Washington is potent, and a proven winner, if given enough time to percolate.

Bill Clinton’s 1992 victory over George H.W. Bush and Ross Perot embodied the elements of the outsider campaign, fueled by free media and a candidate who inherited many of Reagan’s communications skills. The Clinton years come to life in the next post, along with the effect of powerful new forces on the political scene: talk radio and cable news, which preceded the Internet as factors upending the comparatively easy calculus of paid and free media.

~~~~~~~~~~

If you missed earlier parts of the the Story of Polioptics, begin at the beginning with Polioptics Part 1 and Part 2 and Part 3.

And then continue reading The Story of Polioptics. Additional parts of the narrative will appear every few days. When it’s complete, it will be archived it its own section of www.Polioptics.com.

Stay tuned for upcoming posts:

Part 5: Director of Production

Part 6: The 21st Century Presidency

Part 7: The Internet, Pop Culture and the Rise of Obama

Part 8: The First 100 Days…And the Next Thousand

Part 9: Port of Spain

Part 10: Homage to Image

Leave a Reply