Dan Emmett is our guest this week

Show produced by Katherine Caperton.

Original Air Date: March 31, 2012 on SiriusXM Satellite Radio “POTUS” Channel 124.

Polioptics airs regularly on POTUS on Saturdays at 6:00 am, 12 noon and 6:00 pm. Follow us on Twitter @Polioptics

Listen to the show by clicking on the bar above. Show also available for download on Apple iTunes by clicking here.

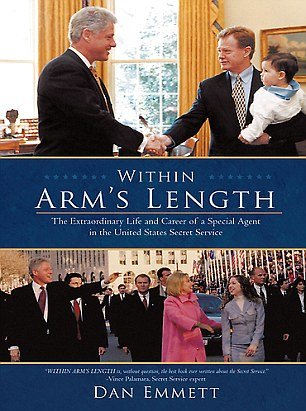

When I learned that Dan Emmett had written a book, Within Arm’s Length: The Extraordinary Life and Career of a Special Agent of the United States Secret Service, I was eager to have him on the show. Last week, we welcomed Pete Souza, the Chief White House Photographer, to our program. Last year, we brought Josh Bolton, former Chief of Staff to President Bush, on the broadcast. When Adam Belmar and I complete episodes with the Chief White House Physician and one of the President’s Military Aides, and maybe a POTUS or two, we will have full representation of what constitutes the major components of the President’s “secure package” in the motorcade. (Dr. Connie, Major Mudd, President Clinton: we’ll be in touch…)

To make the institution of the presidency function, survive and continue, even after a security calamity, all of these people need to work closely together and cooperate even amid competing agendas. The Chief of Staff, and those who work for him, lay out the political and policy strategy of the President, often manifested in the things POTUS does or the places he goes. The Chief White House Photographer creates a visual record of each of those moments. The President’s Military Aide carries “the football,” a satchel containing the codes and protocols for initiating a launch of U.S. nuclear weapons. The President’s Physician is constantly “on call” should the President need medical assistance. And the working shift of the Presidential Protection Detail (PPD) provides 24/7 watch over the President’s security.

To make the institution of the presidency function, survive and continue, even after a security calamity, all of these people need to work closely together and cooperate even amid competing agendas. The Chief of Staff, and those who work for him, lay out the political and policy strategy of the President, often manifested in the things POTUS does or the places he goes. The Chief White House Photographer creates a visual record of each of those moments. The President’s Military Aide carries “the football,” a satchel containing the codes and protocols for initiating a launch of U.S. nuclear weapons. The President’s Physician is constantly “on call” should the President need medical assistance. And the working shift of the Presidential Protection Detail (PPD) provides 24/7 watch over the President’s security.

Even when the President and his family are sleeping on the second floor of the White House, the working shift of the PPD are deployed at key points of the Executive Residence and the 18 acres of the White House grounds to guard their constant safety. Other assets of the PPD, such as the Counter Assault Team (CAT) are standing by in rooms with cryptic names like “W-16” to deploy if needed. On Page 93 of Dan Emmett’s book, which offers not so much an inside dissection of how the Secret Service does its job, but rather a chronicle of a typical career of an agent that could span 20 years or more, Dan expresses little doubt that such a scenario may, someday, be necessary.

“When the day comes for CAT to deploy in a live-fire situation to save the life of a president — and that day will come — I have total faith they will carry the day.”

If you’ve ever seen CAT up close, you know this isn’t a situation in which you want to be in close proximity. This is a team of heavily armed and armored Secret Service Agents that, in Emmett’s era, carried M-16 assault rifles and Sig Saur P226 9MM pistols, in addition to an array of other lethal equipment that rightly remains classified. Should they actually deploy, it would mean that bullets would soon be flying and the only place of possible survival would be prone, face down, in the dirt, and even that’s not guaranteed.

It’s been some time since I lingered around the CAT vehicle in a staged motorcade awaiting a POTUS departure from the White House or other event site, but the mere intimidating presence of the imposing tactical-uniformed squad, compared to the more common mufti of the business-suited agent with PPD lapel pin and earpiece emerging from his or her shirt collar, served as a strong deterrent to all but the most determined and suicidal assailants.

From early 1993 until late 1997, I was a member of the White House staff who regularly worked closely with Secret Service agents like Dan Emmett to plan and execute events that helped the President convey his message in public and simultaneously kept him safe. Indeed, Dan’s tenure and mine overlapped directly for two years, and we worked on, and witnessed, many of the same events, a number of which are in his book.

The two jobs were often at odds, and in his book Dan doesn’t hide his exasperation, at least initially, in how we, trying to do our jobs, made his job more difficult. Consider the situation: the Secret Service has been in existence since 1865 and has evolved its approach and training for the worst case scenario since it began actually protecting presidents in 1901, after the assassination of William McKinley. By contrast, a new White House staff is an organization that only really begins working together at noon on Inauguration Day, and frequently includes people outside the government who serve the President temporarily, either as “detailees” from other cabinet departments or volunteers from the private sector. Within that vast gulf of experience and perspective — the trepidation grown over decades on behalf of the Service vs. the exuberance of often young White House aides who helped to win the presidency in part by making their candidate accessible to the public — there are bound to be conflicts.

The question is, how can both groups co-exist and accomplish their respective goals without completely alienating each other, resulting in a climactic situation that could be severely embarrassing for the President, or much, much worse?

Reading Dan’s book, I got the impression (and he subsequently agreed in his conversation with Adam and me) that this old-school, hard-edged agent, a former captain in the United States Marine Corps, learned by necessity how to roll with the punches working with an Administration whose makeup, from the President on down, was vastly different from the prior 12 years of Presidents Reagan and Bush. Dan entered the Secret Service in 1983, was assigned, as is typical, to investigative duty a field office, frequently “standing post” at many events for President Reagan before coming to the White House as a member of the Counter Assault Team in 1989, which would soon be subsumed into the Presidential Protection Division.

Similarly, the advance men and women supporting the President’s staff with whom I worked also came to appreciate much more, and worked in greater harmony with, the Secret Service Agents who operate with the sole mission of keeping the President alive. We thrived in the 1992 campaign by helping Bill Clinton connect with the masses, whether that meant massive outdoor rallies or midnight rope lines on bus tours across the United States and their seemingly endless impromptu stops to greet gaggles of onlookers who implored Governor Clinton to alight from his vehicle to shake a few hands and, perhaps, say a few words into a hastily configured sound system. The conversation Adam and I had with legendary advance man Mort Engelberg last year recalled the unforgettable thrill of those moments.

In the end, agents with at least a grudging understanding of the political communications imperatives of the White House staff, and advance people with a well-honed appreciation of the threats against the President and the complexities of mitigating them, often developed a rapport that allowed both missions to succeed. I know that was my experience. I thoroughly enjoyed, and deeply respected, many of the agents with whom I worked. Receiving from and collaborating with SAICS like Rich Miller, Dave Carpenter, Lew Merletti, Larry Cockell and Brian Stafford, and the PPD shift members, CAT teams, ID, TSD and CS specialists that worked for them, you could almost always arrive at a compromise that allowed “the shot” to come off as planned, but in the safest way possible. I talk about one such situation on Omaha Beach in Normandy in the 10-part series “The Story of Polioptics.”

Contrary to some of the early reporting on Dan’s book, it’s not a “tell all” about his assignments or the people he protected. In fact, he tells very little, except about himself. Despite some thinly-veiled disdain for political correctness, some people on the White House staff or even within his own agency, he doesn’t spill secrets or compromise methods and tactics used in protection. The stuff of which Dan speaks is pretty much in the public domain, but rolled into one 21-year career that was exposed to just about everything, warts and all.

In the larger sense, I found Within Arm’s Length to be an honest window into the long, at times exuberant and often difficult career of a Secret Service Agent. He talks of the byzantine process of getting hired, the futility of some of the investigative work, the tension that comes from some moments when an agent thinks violence may be at hand, the long hours of sleep and nutrition deprivation (which we, too, experienced) and the frank fact of burnout that often sets in after three or four years on the shift.

Dan does not welcome the kind of window on the Secret Service that has been opened by the competing documentary works of cable networks such as Discovery and the National Geographic Channel, believing that these visual presentations expose too much operational intelligence to potential enemies of the state.

[youtube]HjtrA_OlIGQ[/youtube]

But that access was nevertheless granted by his own agency, and reporters such as Ronald Kessler and Marc Ambinder have gone even deeper with access granted to them in their written journalism about what makes the Service tick.

Somewhere woven into Dan’s experience is the joy and love that comes with being an agent and the situations that a career in the service allows you to experience, but you only really appreciate it when Dan talks about meeting his wife, Donnelle, also a 21-year veteran of the USSS and an Assistant Special Agent in Charge of the PPD. In this regard, Within Arm’s Length is a 200-page recruiting poster for the Secret Service, a career not for the faint of heart.

* * *

Cecil Stoughton’s photo of the swearing in of Lyndon Johnson aboard Air Force One, November 22, 1963

An excellent companion to this week’s show and our conversation with Dan Emmett is found in the April 2 edition of The New Yorker in Robert Caro’s stunning piece, “The Transition,” about how November 22, 1963 transformed the life of Lyndon B. Johnson.

I am wholly incapable of doing justice to Mr. Caro’s work, but if you don’t subscribe to the magazine, this issue is entirely worth your buying at the newsstand, if only to better appreciate the world that Dan Emmett and Pete Souza inherited.

In retelling the day of the assassination of John F. Kennedy from the perspective of his Vice President, Caro paints a fascinating picture of his lead Secret Service Agent, Rufus Youngblood, who enveloped Johnson with his body in the seconds after Lee Harvey Oswald began firing on the President, and the White House photographer, Captain Cecil Stoughton, who shot the iconic photo of Johnson taking the oath of office in the hours after the President was declared dead.

You’re far better advised to read Mr. Caro’s words than suffice with this synopsis, but as Dan Emmett told us, Rufus Youngblood “was on top of his game” on November 22, in what is a dramatic understatement of the day’s events. Youngblood smothered Johnson on the floor of his limousine as shots rang out and stayed there until the motorcade arrived at Parkland Hospital. Once there, Youngblood guided the man who was then, in effect, the new President, through a labyrinthine series of hospital corridors, arriving at a semi-secure room but taking additional measures to guard against what many on the scene thought could be a vast conspiracy to decapitate the government. The decisions Youngblood made at that moment, as what then amounted to the VPPD became the PPD, and the actions he then took to convey Johnson safely back to Love Field and the Boeing 707 with tail number 26000 that served as Air Force One are, through Mr. Caro’s words, one of the greatest feats of fast thinking in the annals of the U.S. Secret Service.

Once on board the plane, the contribution to history of Cecil Stoughton comes into sharp focus, as it were, and Johnson is portrayed as the key orchestrator in what should be considered the most significant moments of Polioptics of the Twentieth Century. Again, just read the piece. It will lay bare how Johnson imagined the import of the world seeing him assume the Presidency through the lens of a camera. He fills the cabin of Air Force One with as many witnesses as will fit in the room, and surrounds himself with three women critical to the drama and the unfolding life of the 36th President: Jacqueline Kennedy, the slain President’s widow; Lady Bird Johnson, his wife; and Judge Sarah Hughes, who administered the Oath (the particular role of Hughes, brought into stark relief by Caro, reveals volumes about Johnson himself). As the congregation gathered, Johnson arrayed the participants in a perfect tableau for Stoughton, who readied himself to take the picture and achieved a level of immortality in the annals of photojournalism (and some would say, propaganda).

* * *

In our recurring segment on Polioptics, “Reading the Pictures,” we are joined in this episode, as we are frequently, by Michael Shaw, founder, editor and publisher of BagNewsNotes.

We begin our conversation on a lighthearted note to discuss the emerging role of the Etch-A-Sketch in political imagery, but quickly move to more somber matters, the evolving optics of the Treyvon Martin killing. As you listen to the segment, you can read Michael’s commentary about the images associated with the Martin case here.

Leave a Reply